From Saxon Pig Farmer to Urban Gentleman, 1868-1937

Posted: June 5, 2018 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: Clara Fischer, Düsseldorf, Elfriede Hoeber, Franz Fischer, Küingdorf 7 Comments

Franz Fischer (standing, center) with his brothers and sisters at the Fischer farm in Küingdorf about 1900. The stern pair at the table are his parents. Franz’ sister Berta holds his arm. Click for a larger image.

My mother’s father, Franz Fischer, for whom I am named, was born on a pig farm in the village of Küingdorf, Germany in 1868, 3 1/2 weeks after his parents married. Located on the border between Westphalia and Hanover ( now Niedersachsen or Lower Saxony ), the landscape around Küingdorf is reminiscent of parts of Vermont or central Pennsylvania. The farm had sufficient land to raise grain to feed the pigs as well as a productive and profitable forest area. The farm was prosperous and well-maintained, but a pig farm all the same,

Franz was the oldest of nine children and in other another area of Germany would have been the heir apparent. It was a peculiarity of the traditional law in the Küingdorf area, however, that a farm was inherited by the youngest son, not the oldest. Thus, Franz knew early on that he would have to find another way than farming to earn his living. So while still a very young man he became interested in that most modern of conveyances, the bicycle.

In 1902, Franz met Clara Schallenberg, a city girl. She was the daughter of a successful retail and wholesale merchant dealing in household china and kitchen ware. Franz and Clara married in 1903.

One of the first things Franz and Clara did when they married was to register as Konfessionslos — without religious affiliation — in the local registry office. This registration would exempt them from church taxes. My mother wrote later of Franz and Clara, “I grew up in a pleasant, peaceful family in which I was taught to have deep disrespect for organized religion and great respect for fundamental ethical principles that none of us would ever abandon. Our father’s principles were rather simple: we do the right things, not to appeal to some figure ‘up there’ in the sky, but simply to do the right thing.” It was a powerful moral rectitude grounded in principled atheism.

Although Franz was born a farm boy, in the city of Dusseldorf he made himself into a gentleman in a time when social mobility was more limited than it is today. While industrialization at the turn of the twentieth century brought substantial migration from farm to city, Franz and Clara took things a step further and entered the Bildungsbuergertum, the literate and cultured middle class. I remember the proud, respectful tone in my grandmother Clara’s voice when she told me Franz was ein richtiger Herr, a genuine gentleman. Clearly one of the things that made Franz a gentleman is that he dressed the part.

As Franz’ business prospered, he and Clara attended concerts and plays, kept a large library and read extensively. Clara could recite long passages from Goethe and other German classics as well as Shakespeare and the Bible, her atheism notwithstanding. Franz and Clara sent their daughter, my mother Elfriede, to the university preparatory school (Gymnasium) and supported her through her PhD. at Heidelberg. Franz embellished his considerable library by pasting a handsome book plate, designed by a friend who was a graphic artist, inside each cover.

Franz and Clara remained committed to bicycling throughout their lives.

Franz died in 1937, well before I was born, but his photographs have made him very real to me. From my mother’s stories about him, he was an easy person to like and was admired by those who knew him.

The Gestapo Has No Sense of Humor – Düsseldorf 1933

Posted: April 18, 2017 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: Düsseldorf, Elfriede Hoeber, Gestapo, Herbert Fischer, Hoeber, Johannes Hoeber, Paul Fischer, Rudolf Hober, Stormtroopers 4 CommentsThe National Socialists took control of the German government on January 30, 1933 and consolidated their power with great speed. Political street violence had been part of German life for a long time, but the Nazis escalated that pattern rapidly and brutally, using terrorist tactics to wipe out political opposition in a matter of weeks. My father, Johannes (1904-1977), was the first victim in our family, when he was arrested in March and imprisoned for several weeks because of his liberal politics, and my grandfather, Rudolf (1873-1953),was next when he was expelled from his professor’s position the following fall, in part because of actions he took against Nazi students. The situation with my mother’s brothers was something else entirely.

My mother had three younger brothers who, in 1933, were in their mid-twenties. All three were good looking and charming, with cheerful dispositions and a taste for evenings with friends in the taverns of Düsseldorf’s Altstadt, taverns with names like the Golden Kettle (Im Goldenen Kessel) and Fatty’s Irish Pub, which are still popular today. On the night of Tuesday, November 7, 1933, my uncles Paul Fischer (1909-1947), a recent law graduate still in training, and Herbert Fischer (1907-1992), by day in business with his father, went out for an evening of socializing. Their father Franz (1868-1937) and older brother Günter (1906-1979) were away on a business trip for several days.

Herbert Fischer (1907-1992). This picture was taken several years after his imprisonment by the Gestapo in 1933.

The social evening lasted until 3 :00 in the morning, when the bars closed. Paul and Herbert, whose state after a long night of drinking can only be guessed, got into the car of a friend who drove them home. Still joking as they tumbled out of the car, Herbert spotted a poster that had been pasted on a nearby wall and was partially coming off. Tearing the poster off the wall, Herbert crumpled it into a ball and threw it into the car at his friend saying, “Here! You can use this to clean your windshield!” It seems that Herbert didn’t recognize the poster as Nazi propaganda, nor did he notice the Stormtrooper watching nearby. Although lacking legal authority, the hundreds of thousands of brown-shirted Stormtroopers of Hitler’s Sturmabteilung constituted a militia of the Nazi Party and were free to attack and bully citizens who showed any sign of dissent from the regime. Although Herbert was non-political, the waiting Stormtrooper saw his petty vandalism as a political act and took him into custody. Paul went along to be a witness in his brother’s defense, but soon found himself taken into custody as well.

Paul Fischer (1909-1947). This picture was taken a couple of years after his imprisonment by the Gestapo in 1933.

As Paul and Herbert got passed on from the Stormtrooper to a bicycle policeman to an automobile police squad to the police station, the story of the incident grew from a tipsy prank to an organized conspiracy against the state. By dawn, both Herbert and Paul were arrested and imprisoned and their case turned over to the “political police,” a part of the recently formed Secret State Police (Geheime Staatspolizei or Gestapo). Apparently the fact that Paul was a lawyer in training (Referendar) increased the Gestapo’s suspicions. The brothers were held for more than a week without charges and were subject to repeated beatings.

The day after the arrest, my grandmother and my father and mother began agitating with the police for the young men’s release. It took three days just to identify the official with authority over Paul and Herbert’s case. My grandmother was so desperate for her sons’ release that she forced herself to mumble “Heil Hitler!” to the police official, the only time in the entire Nazi period that she ever used that hated salutation. As my father wrote at the time, “Endless approaches, endless waiting, walking down endless corridors, daily hopes, daily disappointments, long negotiations and discussions, after the third day with the help of a lawyer.” After a week, Paul was released with no explanation either for his arrest or his beatings or his release. He left the city immediately to recuperate from the wounds he received in the beatings. Herbert continued to be held, inexplicably, because, as my father wrote, “He never at any time ever engaged in any political activity whatsoever.” Nevertheless, it took another week to negotiate his release, again without explanation, but, as my mother wrote, he came out “relatively undamaged.”

In the end, it all came to nothing and the brothers returned to their respective occupations. But the reality of being arrested and beaten and held for many days for no reason was part of the atmosphere of terror that would be part of daily life in Germany for the next 12 years.

Johennes Höber’s letter to his parents telling of the Gestapo’s arrest of his brothers-in-law, Herbert Fischer and Paul Fischer, on November 8, 1933. (Deutschleser: Bitte klicken für ein größeres Bild.)

More stories about the Hoeber and Fischer families are to be found in Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939, published by the American Philosophical Society. Information is available here. Also available at Amazon.com

A Story in Some Grains of Sand

Posted: July 6, 2016 Filed under: Hoeber | Tags: Baltic Sea, Delft vase, Elfriede Hoeber, Hoeber, Immigrant experience, Jacob Marx, Johannes Hoeber, Josephine Hober, kiel physiological institute, Rudolf Hober, Susanne Hoeber Rudolph, University of Kiel Leave a commentWhen I went to my late sister Susanne’s Vermont home recently, I spotted this familiar old family vase. I placed it on a table on the sunny porch to photograph it. Then, with relatives watching, I turned the vase over and poured out — some ordinary sea sand.

How did I know there would be sand in the vase? The answer is a story I heard from my father a long time ago.

My great-grandfather, Jacob Marx, was a banker and investor in Berlin in the mid-nineteenth century. He made some smart investments in the industrial boom before and after the Franco-Prussian War in the early 1870s. Some of his new wealth he invested in art, including several antique Delft vases.

After Jacob died in 1883, the vases were owned by his widow, Marie, and when she died in 1913 they were inherited by my grandparents, Rudolf Höber and Josephine Marx Höber. At that time, Rudolf and Josephine lived on Hegewischstrasse in Kiel, a university city and naval harbor on the Baltic Sea.

Rudolf and Josephine Höber with their first child, Johannes, around December 1904 (ten years before they inherited the Delft vases).

Josephine displayed the vases atop a tall Schrank, an antique wardrobe cabinet in the family living room. Inconveniently, however, a streetcar line traversed the street in front of the residence, and every time a trolley went past the Delft vases shook and rattled. The noise annoyed Josephine, who also feared the old pieces would be shaken off the cabinet and break. To resolve the problem, she gave her ten-year-old son Johannes a metal pail and told him to go down to the shore of the Baltic, fill the bucket with sand and bring it home. Josephine then filled each Delft vase with sand. The extra weight kept them from rattling on top of the Schrank for the next 19 years.

In 1933, the Nazis forced Rudolf out of his position in Kiel and he and Josephine emigrated to Philadelphia. They took the vases with them — and the sand went along. Josephine died in 1941 and Rudolf in 1953 and then the vases — and the sand — were inherited by my parents, Johannes and Elfriede. They moved several times and at each move the vases were carefully packed and the sand with them.

Johannes died in Washington DC in 1977 and Elfriede in Oakland, California in 1999. When we divided up Elfriede’s possessions among her three children, my sister Sue expressed a desire to have the Delft vases. We wrapped them and transported them — and the sand — to the house in Barnard, Vermont, where she and her husband Lloyd worked and wrote in the summers for many years. And there they have remained until now. The next home for the Delft vases and the sand from the Baltic Sea remains to be seen.

Susanne and Lloyd Rudolph’s house in Barnard, Vermont, the last stop so far in the Delft vase’s journey.

More stories about the Hoeber family are to be found in Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939, published by the American Philosophical Society. Information is available here. Also available at Amazon.com

Review of “Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939” from CHOICE, A Publication of the Association of College and Research Libraries

Posted: May 2, 2016 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: Against Time: Letters From Nazi Germany 1938-1939, American Philosophical Society, Destruction of Duesseldorf, Elfriede Hoeber, Escaping Nazi Germany, Francis W. Hoeber, Hoeber, Immigrant experience, Immigration visa, Johannes Hoeber, Letters from Nazi Germany, Philadelphia reform movement, Susanne Hoeber, Susanne Hoeber Rudolph 1 Comment

I am delighted that the following review appeared on May 1, 2016, in CHOICE, a publication of the Association of College and Research Libraries.

REVIEW

AGAINST TIME: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939, by Francis W. Hoeber

Francis Hoeber possesses, apparently, decades’ worth of materials from his family’s history. However, he has chosen to publish only letters from 1938 and 1939, because they are truly exceptional in foregrounding human experience in the face of obliterating fascism. His father, Johannes, had emigrated from Germany in 1938, with the idea that Elfriede would follow with their young daughter. Complications arose. Eventually they united, lived in the US, and raised their family. That is a passive, objective summary. In contrast, these letters, written by two literate, gifted writers, construct a deeply experienced history entwined with significant world events. Genuine, emotional, human, rational—the letters exemplify precisely why published history needs such primary material. We can read or view synthesized historical accounts in textbooks or documentaries; we can summarize and categorize, intellectually. However, only by absorbing the personal narratives of people who recount the events they lived through can readers approximate the feelings, the vibrant presence, the individual acts that enliven historical experience. Through self-expressed microhistory, whether routine (running a business) or epochal (Kristallnacht), readers feel the macrohistory viscerally. Hoeber provides relevant context in footnotes and summaries to orient readers.

Summing up: Highly recommended.

–J. B. Wolford, University of Missouri—St. Louis

More information about Against Time is available by clicking here.

You can order the book directly from the publisher by clicking here.

Also available at Amazon.com

A Surprising Perspective on America — 1937

Posted: April 25, 2016 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: Cape Cod, Chatham MA, Düsseldorf, Elfriede Hoeber, Escaping Nazi Germany, Fiorello LaGuardia, Hoeber, Johannes Hoeber, Josephine Hober, Philadelphia, Rudolf Hoeber, university of pennsylvania 2 CommentsRudolf and Josephine Höber, my grandparents, fled Nazi Germany for Philadelphia already in 1933, but their son Johannes and his wife Elfriede were holding on in Düsseldorf in the belief that the Nazis couldn’t last. By 1937, my grandparents were desperate to have their children join them in America, so Rudolf and Josephine invited the young couple to come and visit them in America. It turned into a grand trip.

Steamship Europa in Cherbourg, France. Photo by Johannes Höber, May 1937 as he and Elfriede were leaving for a month in the US.

Elfriede kept a travel diary capturing her impressions of the country that would later become home to her and Johannes and their little girl, Susanne.

Elfriede complained on every page about the “unbearable,” “insane” heat (Washington and Philadelphia before air conditioning) but otherwise she and Johannes found much to like in America. They were impressed by Washington, where many of the iconic government buildings along the Mall had recently been finished, and they liked the democratic feel of the place.

Elfriede: “We drove by the White House as though it were an ordinary residence. No guards to be seen. Unfortunately Mr. Roosevelt was not at home.”

In Philadelphia, the family attended the graduation of Johannes’s sister, Ursula, from the University of Pennsylvania medical school. They were impressed by the 1,500 graduates and the audience of 8,000 in Philadelphia’s Convention Hall, with Roosevelt’s Secretary of State Cordell Hull as commencement speaker.

Elfriede loved Connecticut: “This is the way I always imagined New England to be, with hills and forests scattered with enchanting villages with white wooden houses and white churches on trim green lawns under high trees. The houses are mostly laid back from the street and not separated by fences. As a result the country seems so open and gains a wonderfully elegant and fresh appearance.” In Woodbury, Connecticut, they asked directions of a police officer. “This guy was like a sheriff in the movies, going around in short sleeves with a big tin badge, unshaven, and stormed off in the middle of our conversation and threw himself into his car to chase another car that had exceeded the Woodbury speed limit.” The family drove from Philadelphia to Cape Cod in two cars, a Ford and a DeSoto, where Elfriede declared the beaches to be the loveliest she had ever seen.

Johannes and Elfriede traveled from Cape Cod (Fall River MA) back to New York by night boat! Elfriede: “Excellent cabin on the Commonwealth, a very old fashioned but very comfortable ship. Wonderful evening ride to Long Island Sound. Fantastic passage through the ocean of lights of the harbor of Newport. Night’s sleep interrupted by foghorns. Awoke at 6:15 in the East River. Reunion with the Empire State Building. Passage under the East River bridges that cross the river in great arches, all with two levels with eight lanes each. Generous good breakfast on board to prepare us for a day in New York.”

One of the steam boats of the Fall River Line that carried passengers between Cape Cod and New York until 1937.

Johannes and Elfriede spent their last America day in New York, where Johannes indulged himself three times in “America’s national drink” — an ice cream soda. Elfriede: “Lunch in an enormous restaurant. The ladies room has 60 toilets, 30 for free and 30 for 5 cents. The noise of the streets is mind shattering. The noise of the El is deafening, the subway hellish. The people in this city seem to have lost all sense of hearing.”

And a highlight of the whole trip, an hour before they boarded the ship to return to Europe, was to go by New York’s City Hall and catch sight of Fiorello LaGuardia, whose reputation as a dynamic, progressive mayor had reached even into the corners of Hitler’s Germany. “We were able to watch as LaGuardia stood next to his car for a few minutes talking with advisers. Because we were speaking German, a man appeared next to us out of nowhere, unmistakably a cop, and didn’t let us out of his sight until the mayor left.”

Elfriede and Johannes returned to Düsseldorf in late June 1937, but the visit to his parents bore fruit. Six months later, Johannes and Elfriede began making their own plans to leave Germany and move to the United States. It would be nearly two more years, however, before the whole family could be reunited in Philadelphia.

Elfriede and Johannes Höber at home in Düsseldorf in 1938, a few months before Johannes left Germany permanently to live in the United States. Elfriede and Susanne followed him a year later.

The story of how Johannes and Elfriede eventually got out of Germany and into the United States is told in Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939. You can read more about that book here. Also available on Amazon.com.

Through Books, Immigrants Become Americans. 1939 …

Posted: March 17, 2016 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: Baedecker, Dr. Spock, Elfriede Hoeber, Escaping Nazi Germany, Huckleberry Finns Fahrten und Abenteuer, Immigrant experience, Johannes Hoeber, Kenneth Roberts, Letters from Nazi Germany, Philadelphia history, Rudolph Blankenburg, Scharff and Westcott Leave a commentIf you’re pretty well educated in your birth country, it’s daunting to face a new country and become a person who knows less than anyone else. So how do you catch up? When my parents decided it was time to flee Nazi Germany, their answer was books. I still have some of them. I love this beautiful history of the United States, with its funky canvas dust jacket and the stars on the spine:

My mother’s mother gave her fleeing daughter and son-in-law this old Baedeker’s guidebook to the United States, in English. The fold-out city maps are small but quite detailed. Years later my mother fell in love with the Rand McNally Road Atlas, but in the beginning it was this Baedeker that got her and my father started on American geography:

Baedecker’s United States. This fold-out map of Washington D.C. is one of 50 maps in the book. Click for larger image.

What do you give a bright eight-year-old to learn a bit about adventures in America? The choices in Nazi Germany weren’t too great, but you could do worse than providing her with a German translation of an American classic — Huck Finn. Susanne learned to love Mark Twain’s stories of life on the Mississippi well before she got here:

And how do you learn to raise children the American way? A couple years after arriving here, my parents were confronted with two new babies in short order — my brother and then me. Fortunately, every American at the time followed the same child-rearing Bible, Dr. Spock. That my mother referred to it frequently is shown by the tattered condition of this cheap paperback edition. She must have been comforted by the first eight words of the book, one of the most uplifting opening sentences of any book ever: “You know more than you think you do.” The simplest reassurance imaginable.

German schools didn’t teach much about the American Revolution, so even educated immigrants didn’t know much about early American history. A German friend who had arrived in America a couple of years earlier than my parents introduced them to the historical novels of Kenneth Roberts set in the American Revolution and the years of the Early Republic. Roberts was a fine historian as well as a novelist, and my parents learned more than many Americans about our early history in a short time from his books. Because of him they loved to visit historic sites in the U.S., starting with Valley Forge shortly after their arrival:

Oliver Wiswell (1940 ), Rabble in Arms (1933 ), Lydia Bailey (1947 ) by Kenneth Roberts. My parents learned a lot of American history from these novels.

My mother, particularly, developed an interest in the history of Philadelphia. She was fascinated to learn that in the early 20th century Philadelphia was governed by a German-American progressive named Rudolph Blankenburg. At Leary’s huge used book store on 9th Street above Chestnut, she was able to by a book on Mayor Blankenburg, written by his wife, for half a dollar:

The Blankenburgs of Philadelphia (1928), by Lucretia Blankenburg. Mayor Blankenburg was called “Old Dutch Cleanser” because of his work cleaning up ocrruption in Philadelphia.

When my parents had been in the U.S. for some time, my mother acquired her great treasure, a copy of Scharf and Westcott’s magnificent three-volume History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884. Standards of historical accuracy were different when this set was published, but it is still a wonderful source of anecdotes about the city in its first 275 years:

History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884 by J. Thomas Scharff and Thompson Westcott, 1884. My mother also bought this set at Leary’s Used Books on 9th Street for $25 around 1955.

History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884 by J. Thomas Scharff and Thompson Westcott, 1884. Click on image to view more clearly.

More on the Hoeber family is in the book Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939. Click here for details and ordering information.

A Conversation — Finding Refuge in America: Germans 1939, Syrians 2015

Posted: November 26, 2015 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: American Philosophical Society, Düsseldorf, Elfriede Hoeber, Escaping Nazi Germany, Hoeber, Immigrant experience, Immigration visa, Johannes Hoeber, Letters from Nazi Germany, refugees Leave a comment

Johannes Höber and Elfriede Höber shortly before their departure from Germany for America, 1938

Americans are schizophrenic about immigration. We have two contradictory traditions with respect to people from other countries who come here to live. On the one hand, we have the Emma Lazarus, tradition: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore … ” and so on. This welcoming tradition dates as far back as William Penn, whose 1701 Charter of Privileges welcomed people of all nationalities and religions to come and live in his Quaker colony in America. On the other hand, America has an equally strong xenophobic tradition, from the Alien Enemies and Naturalization Acts of 1798, through the nativist Know Nothing Party of the 1840s and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, to the restrictive Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 and the proposal today of a leading candidate for president of the United States to physically deport 11 million migrants by force. For more than two centuries, persons wanting to come here from abroad to live have encountered these contradictory impulses in American culture—welcoming and exclusionary—when trying to secure permission to immigrate.

Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939, by Francis W. Hoeber. Published by the American Philosophical Society Press, September 2015.

In the process of escaping Hitler and finding refuge here, my parents encountered both of these contrary American traditions. My book, Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939, illustrates the realities for a family negotiating what was ultimately an arbitrary U.S. immigration process as well as the day-to-day personal impact of migration under pressure. My parents got out of Germany and into the U.S. as the result of their education, hard work and good luck. But if it had not been for generous Americans who enthusiastically supported refugees who wanted to become part of the American fabric, their story could easily have turned out differently.

On November 22, 2015, I spoke with radio producer Loraine Ballard Morrill in Philadelphia about Johannes and Elfriede’s experiences in getting into the United States as they sought to escape Germany in 1938 and 1939. The conversation led to a discussion about the parallels between anti-immigrant rhetoric in the 1930s that led to the restrictions on refugees in that period and the politics of exclusion of Syrian refugees in 2015. You can hear the interview by clicking here.

Rebuke from Alaska

Posted: September 30, 2015 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: Alaska, Athabaskan, Elfriede Hoeber, Grayling, Housing Demonstration Program, Moose meatloaf, Yukon River 4 Comments

Town of Grayling, Alaska with the Yukon and the town airstrip. Obviously there’s lots of forest. Photo is dated 1999.

My readership spiked hugely one day recently. The platform I use for this blog gives me daily statistics on the number of readers, identifying the country in which the readers are located and the posts they hit. A two year old post, originally captioned “New Houses for Eskimos — 1966”, suddenly got more hits in one day than the whole website usually gets in a week. Then two comments popped up on that post. The first read:

“First off, we are not Eskimo. Second, your mother put our moose meat down. Third, it is not the tundra. AND YES! We have trees. So before you publish something like this, you should do your research.”

The second comment read,

“First of all, we are [not] Athabaskan Eskimos, we are Athabaskan Indians. Your article is incorrect on so many topics and disrespectful on so many levels. Before you blog about any community or tribe you should travel to that community and do your research yourself. You have no right to stand in judgement of another race or community and publicly put that race or community down to such levels of disgrace. This type of public discrimination should be banned.”

I was mortified. The post was based on a report to the federal Housing Demonstration Program that my mother wrote when she visited two housing sites in Alaska in 1966. She loved that trip and the people she met, and retold the story many times over the next 25 years. It’s true that she used the word “Eskimo,” which was the government’s designation of the people at that time; the government subsequently learned better. The Athabaskans who wrote me had reason to be angry; no one wants to be called by the wrong name. It’s also true that my mother used the word “tundra,” though when I checked I found she used that description for only one of the two towns she visited. The other was clearly in a forested area. The mistake was mine. As to derogatory comments about moose meatloaf, well, the readers got me there. Though the remark was rude, I think it’s not unusual and not the worst offense if someone doesn’t care for food they’ve never eaten before. That has been a common experience among travelers since people began to travel. The truth is, though, that I would like to try moose meatloaf.

I wrote back to the two commenters to apologize as best I could for the errors in the post. The answer I got back from Stacy made me feel a little better — and made me want more than ever to visit that town in Alaska that meant so much to my mother half a century ago. She wrote:

I’ve decided that I would respond after a long day of thinking about this entire blog. I’d like to thank you for responding to my comment. I think it is very nice of you to try and make this blog more accurate than previously written. It would take a very long time to actually explain all the details of what my father’s homeland really, truly is. However, I will say this – unless, you’ve been here in Alaska yourself and went into someone’s home and actually stayed more than a week, it’s hard to sum up our traditions, food and overall life. We are very easy-going people, who work hard on a daily basis to keep the kids and elders fed. Once that happens, if we have time for ourselves after a long day, we may start on some arts and crafts or the men may play a game of poker. Anyway, like I said – until you’ve experienced Alaska yourself, it’s hard for me to sum up what it’s actually like to visit at someone’s house over tea, eat smoked salmon strips, crackers and walking away with the endless smiles and happiness you feel in your heart after a really good visit filled with laughter and fun!

Moose wading in Grayling Lake, Alaska. Some day I would like to try the moose meatloaf made by the local folks.

If you like the stories on this website, you may be interested in Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939, by Francis W. Hoeber.

Details and ordering information are available by clicking this link.

Stymied in Antwerp – October 1939

Posted: August 14, 2015 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: American immigration visa, American Philosophical Society, Antwerp, Düsseldorf, Elfriede Hoeber, Escaping Nazi Germany, Johannes Hoeber, Letters from Nazi Germany, Naz passport, Susanne Hoeber 3 Comments

Elfriede Höber and Susanne Höber on the balcony of their apartment at Pempelforterstrasse 42, Düsseldorf, December 1938.

World War II began with Hitler’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. My mother, Elfriede, and my 9 year old sister, Susanne, were living in Dusseldorf and getting stuck in Nazi Germany became an all-too-real possibility for them. It was imperative that they get away and join my father, who had fled to Philadelphia the previous year. The war had started just a few weeks after the American consul had granted Elfriede and Susanne immigration visas after months of struggling. Then, getting the household packed up, wrapping up their business, and saying farewell to family and friends took weeks — and suddenly it was almost too late.

The start of the war only increased the flood of emigrants racing to escape Europe. The stamps in Elfriede’s passport show that on September 14 she paid the German government 8 Reichsmarks for an exit permit. On September 19 she obtained a bank certification for the 20 Reichsmarks (about $10), the total that she was allowed to take out of Germany. Thankfully, on September 22 at 8:50 P.M. she and Susanne crossed the border at Aachen out of Germany and into Belgium. They arrived in Antwerp the same day, where they were supposed to board a ship for America. But it wasn’t that simple.

Stamps in Elfriede and Susanne’s passport show their exit permit, fiscal authorization and crossing of the border into Belgium, September 1939.

The first days of the war saw numerous naval battles between Germany and Great Britain, including the sinking a British warship with a loss of 700 lives. The fighting at sea completely disrupted civilian shipping in the English Channel and the North Atlantic. As a result, Elfriede and Susanne’s ship was delayed again and again. Day after day they trekked to the shipping office of the Holland America Line, which was besieged by hundreds of refugees desperate to escape Europe. Seventy-five years later, Susanne still remembers the grimy hotel, the chaos at the shipping office, the fear and the grinding boredom of the wait. Finally, however, after weeks of waiting, Elfriede was able to confirm their passage on the S.S. Westernland that ultimately left on October 28. She sent off a letter to her husband, Johannes, in Philadelphia, with the news. After explaining the complicated arrangements with finances and ships, she added,

How have these things been with you all these weeks? At this point I’ve heard almost nothing about you for two months, but now it seems like we’ll actually get out of here and get to you. I hope we don’t run into any disaster other than seasickness on the way, because as [my brother] Paul aptly noted, you can take Vasano for seasickness but for torpedoes you can only take a lifeboat. To tell the truth, I’m not really very worried about the torpedoes. When cautious people at home asked me whether I was really going to risk the transatlantic trip at this time, I just answered that it was pretty much the same to me whether a bomb fell on my head in Düsseldorf or a torpedo hit some other part of my body on the ocean. On the other hand, a bomb shelter is warmer than the North Atlantic in October. …

If heaven and assorted Führers don’t spit in our soup again, we’ll be with you in a couple of weeks.

Alles liebe Deine Friedel

The story of what happened next, and more about Elfriede and Johannes’ flight from Germany to the United States, is contained the book from which this story is taken: Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939, available by clicking here.

An Inventory of a Life Together — A Requirement to Leave Nazi Germany, 1939

Posted: March 25, 2015 Filed under: Hoeber | Tags: Duesseldorf, Elfriede Hoeber, Escaping Nazi Germany, Johannes Hoeber, Reichfluchtsteuer, Susanne Hoeber 1 CommentAs I await the publication of Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939, the story of my parents’ emigration to the United States, I am trying to give readers here an idea of what was involved in those tense times. There were difficulties from both sides: the Germans made it hard to get out and the United States made it hard to get in.

German policy for all practical purposes allowed taking only 10 % of cash, stocks or valuables out of Germany. Two departure taxes, the Gold Discount Bank Fee [Golddiskontobankabgabe] and the Nation Abandonment Tax [Reichfluchtsteuer] amounted, in effect, to the expropriation of up to 90% of the liquid assets of emigrants. Jewelry, silver, artworks and similar valuables were subject to the same taxes to prevent people from turning their money into objects they could export.

Inventory of the household effects of Johannes and Elfriede Höber required by the Nazis as a condition of leaving the country. August 9, 1939.

What was permitted was the export of household belongings and personal effects sufficient for a “modest life” [bescheidende Existenz] in the émigré’s new country. Anyone planning to move out of Germany had to file a detailed inventory of everything they owned before they could get a permit to leave. The normal method of shipping was by having a moving company pack the entire household into an enormous crate that would then be transferred by crane to a ship and transported by sea. When the crate reached the United States, the household goods would be transferred to a truck and delivered to the new residence.

My father came to the United States in December 1938 but my mother and my then nine-year-old sister were not able to leave Germany until late the following year. In August 1939, my mother prepared the household for shipping, and prepared the required inventory, a copy of which she later brought with her to America.

The inventory was insanely detailed, down to “one wash line and clothes pins,” a trash can, a honey jar, a cookie box, six dust cloths, and a box of cloth remnants for patching holes in worn clothing. My parents were both then age 35 and had been married for ten years. The inventory illuminates the lifestyle of a middle-class European family of the 1930s. Thus, the inventory includes furniture, beds and bed linens, china and silverware, kitchen utensils and other items of daily life, but also a dozen each of wine glasses, champagne glasses, beer glasses, punch glasses and liqueur glasses. My parents’ leisure activity is shown in the listing of two pairs of skis and two pairs of ski boots as well as two pairs of hobnailed climbing shoes, a rucksack and a pair of mountaineering pants — and a picnic basket and its contents. Most revealing to me was the inclusion on the list of 800 books — mostly on economics, art history and fine arts — as well as 100 children’s books, a pretty good personal library for a nine year old.

My sister, Susanne Höber, as a little girl in the Alps. The inventory of our family’s belongings showed they were people who enjoyed the mountains and also that our parents gave her lots of books.

You can read the full 5-page inventory here: Inventory August 9 1939 — English translation . One of many ironies of my parents’ life is that none of these carefully cataloged belongings ever got out of Germany. My mother was still in Düsseldorf when Hitler started World War II by invading Poland on September 1, 1939. As a result, no ships were available to transport the crate of household belongings to the United States. With no other choice available, my mother had everything put in storage and fled. Everything, from furniture to books to dust cloths, was destroyed during the Allied bombing of Düsseldorf on June 12, 1943.

75th Anniversary of a Memorable Day

Posted: November 5, 2014 Filed under: Hoeber | Tags: American Philosophical Society, Elfriede Hoeber, Escaping Nazi Germany, Germantown Philadelphia PA, Hoeber, Immigration visa, Johannes Hoeber, Susanne Hoeber 1 CommentToday, November 5, 2014, marks the 75th anniversary of the day my mother, Elfriede Fischer Höber, and my sister Susanne Höber, arrived safely in the United States from Nazi Germany. They had made a narrow escape weeks after World War II had begun.

In the spring of 1939, Elfriede and Susanne, then age 9, had found themselves stranded in the north German city of Düsseldorf. My father, Johannes, had come to Philadelphia a few months earlier to prepare the way for them. In the intervening period, the Nazis continued to tighten the screws on the German population and threatened to plunge Europe into war. The pressure was getting extreme for the hundreds of thousands who wanted to leave the country. On June 22, Elfriede succeeded in getting a new passport for both her and Susanne.

Passport issued by the German authorities for Elfriede Fischer Höber and Susanne Höber on June 22, 1939 .

The greater difficulty, however, was to get a visa allowing them to enter the United States. American law at that time permitted only 27,000 Germans to obtain immigration visas annually. In 1938 alone, over 300,000 Germans applied for visas, meaning that hundreds of thousands of people desperate to leave the country were denied admission to the United States. Liberal legislative efforts to expand the number of German refugees allowed into the United States were stymied by a coalition of Southern congressmen, anti-immigration groups, isolationists and antisemites (since a majority of those seeking admission were Jews). The denial of entry to the U.S. doomed thousands who might otherwise have survived the Nazis.

Elfriede and Susanne were among the lucky ones. After months of struggling with visa applications and mind-numbing paperwork both in Germany and the United States, they were summoned to the office of the U.S. Consul General in Stuttgart on July 12, 1939. The last step in the application process was a physical examination, which both of them fortunately passed. When the examination was done, a clerk used a rubber stamp to imprint two immigration visa approvals on a page of the passport, using quota numbers 608 and 609. Vice Consul Boies C. Hart, Jr.’s signature and the embossed consular seal on each imprint made them official. Elfriede and Susanne now had had the wherewithal to escape to safety and freedom, a chance denied to countless others.

Logistical issues made it impossible for Elfriede and Susanne to cross the German border into Belgium until September 19, by which time Germany had attacked Poland, and Britain and France declared war on Hitler. It took another six anxious weeks in Antwerp before they were finally able to board a ship for America. It is hard to imagine their joy and relief when they were reunited with Johannes on a pier in New York harbor on that day three-quarters of a century ago.

The full story of Elfriede and Susanne’s escape is told in the book Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939 published by the American Philosophical Society. Click here to learn more about the book.

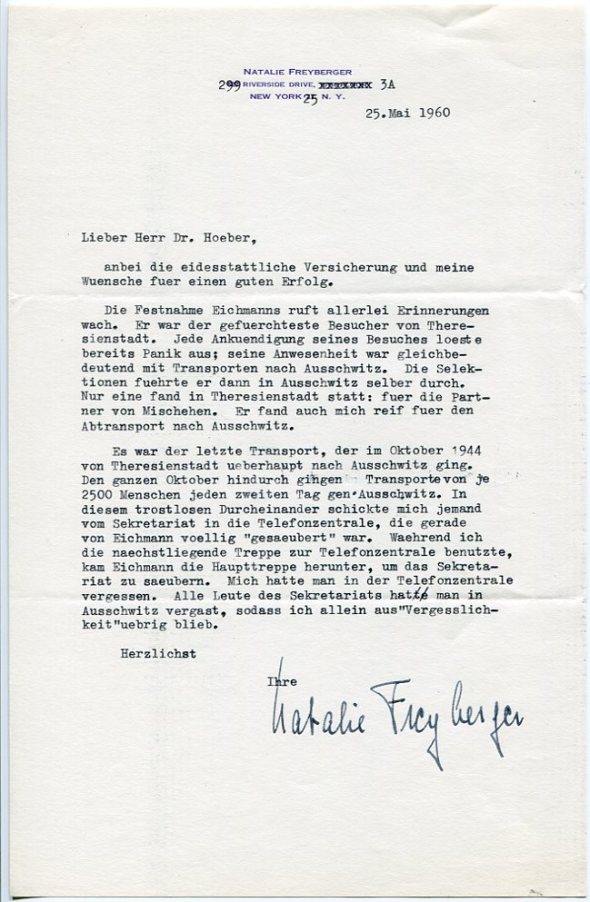

Her Life Spared by Happenstance, 1944

Posted: October 6, 2014 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: Adolf Eichmann, Auschwitz, Elfriede Hoeber, Escaping Nazi Germany, Johannes Hoeber, Natalie Freyberger, Theresienstadt 2 CommentsMy parents, Johannes and Elfriede Hoeber, were fortunate in escaping Nazi Germany. The story of how they got out in 1938-1939 is the subject of the book Against Time: Letters from Nazi Germany, 1938-1939 to be published next year. Not all of their friends were as fortunate as they. When I was working on the book, I found a letter among my parents’ papers that told the astonishing story of a close friend of theirs. The letter was written to my father in 1960, during the time when Adolf Eichmann was on trial in Jerusalem.

Natalie Freyberger was a bright young woman who lived in Düsseldorf when my parents did. She worked part time for Johannes and Elfriede as a secretary in their small newspaper distribution business (the Nazis having expelled my father from his government post years earlier). Because she was completely reliable, Johannes and Elfriede could leave Frau Freyberger in charge of the business for a couple of weeks when they had to be away. Like many of Johannes and Elfriede’s friends, Frau Freyberger was Jewish. Early in 1939, her non-Jewish husband divorced her under the Nuremberg laws, which made marriages between Jews and non-Jews illegal. Frau Freyberger desperately wanted to leave Germany but was unable to do so because she couldn’t find a country that would let her in. Some time after my parents left Germany, Frau Freyberger was arrested and transported to the concentration camp at Theresienstadt. The story of how she managed to survive is told in the letter she wrote my father many years later:

May 25, 1960

Dear Dr. Hoeber,

* * * * *

Eichmann’s arrest has aroused all sorts of memories. He was the most feared visitor to Theresienstadt. Every time there was an announcement of his visit it set off a panic; his presence meant the same thing as transports to Auschwitz. He then carried out the selections himself in Auschwitz. Only one of them took place in Theresienstadt: for the spouses of mixed marriages. He found me suitable for removal to Auschwitz too.

It was in October 1944 that the last transport ever went from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz. All through October there were transports of 2500 people to Auschwitz every second day. In this desolate confusion someone dispatched me from the main office to the telephone center, which had just been completely “cleansed” by Eichmann. While I was using the nearest steps to the telephone center, Eichmann was coming down the main stairway to “cleanse” the main office. They forgot about me in the telephone center. Everyone who was in the main office was gassed in Auschwitz, so that I alone remained as the result of “forgetfulness.”

Sincerely,

Your

Natalie Freyberger

How do You Raise a Bright Little Girl in Nazi Germany?

Posted: September 2, 2014 Filed under: Hoeber, Uncategorized | Tags: Düsseldorf, Elfriede Hoeber, Erich von Baeyer, Escaping Nazi Germany, Johannes Hoeber, Rhineland Karneval, Susanne Hoeber Rudolph 2 Comments My sister, Susanne Hoeber Rudolph, lived in Düsseldorf , Germany until she was nine years old . She was just three when the Nazis took over the country and our family lived there under Hitler’s regime until 1939. At that time our parents, Johannes and Elfriede, took Susanne to America. I am always amazed when Susanne tells me that she experienced her childhood as a happy one, full of friends and secure family connections. Our grandmother on our mother’s side lived nearby as did two of Elfriede’s younger brothers, with whom Susanne was great friends. She enjoyed school and her school friends and was well taught. Johannes and Elfriede’s circle of interesting grownup friends formed a warm background to Susanne’s daily life. These family and social circles managed to shield Susanne from most of the oppressive conditions created by the Nazis.Although our parents were nonreligious — Konfessionslos in German — Düsseldorf was a Catholic city and our family measured life around the celebration of the holidays of the Christian calendar — Lent, Easter, Pentecost, St. Martin’s, Advent, Christmas. The Karnival season in late winter — the German equivalent of Mardi Gras — was celebrated raucously in Düsseldorf and the surrounding Rhine valley. Rosenmontag, the Monday before Ash Wednesday, was celebrated with a huge costumed parade in which children participated as well as adults. For Rosenmontag in February 1939, Susanne decided she wanted to dress as a Mexicanerin, a Mexican cowgirl. Her grandmother helped her assemble all the accessories for her costume — wide skirt, big belt, checked shirt, kercheif and a broad-brimmed hat. Elfriede tracked down the makeup Susanne wanted as well as a cap pistol (despite Elfriede’s pacifist aversion to such toys). The final charming effect was documented both in a photograph by Susanne’s Uncle Günter and in her own self-portrait drawing.

Had Johannes and Elfriede remained in Germany, Susanne would have been required to enter the Hitlerjugend, the Nazis’ corps for indoctrinating children in the fascist ideology of the Third Reich. Protecting her from such an intolerable experience was one of the many reasons our family fled Germany.

POSTSCRIPT: After I wrote the piece above, I sent it to Susanne to review. She liked it, and sent the following additional story. Note that this is a memory from 75 years ago:

![Erich von Baeyer, "Portrait of a Young Girl" [Susanne Höber], 1938](https://hoebers.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/susanne-von-baeyer-portrait.jpg?w=590&h=714)